It’s a natural and classically human desire to stand victoriously on top of the podium. Even if we don’t admit it, just about everyone internally wants to be the best at something.

Some people want to be great athletes, while others desire admiration for their works of art. No matter what the domain, the idea remains the same: we all want to be (or at least considered) great.

Taking a page from the con artist handbook, many popular public figures have latched onto this age-old emotional vulnerability to build entire industries.

Millions of dollars are being spent every year on books, courses and coaching to help people become “world-class performers.”

Hell, that’s what I started out wanting to do. My first book, The Learning Factory, is a guide for building up skills and knowledge in the most efficient way possible, largely because I wanted to be able to develop world-class skills.

I even put my system to the test when I learned how to program and got my first job in the industry in less than a year.

I started that journey several years ago, and I can safely say that I’m not a world-class programmer. I don’t even write code on a regular basis anymore, aside from the odd Python or JavaScript hack.

But I can say, without a doubt, that getting to a journeyman level of skill opened up a world of opportunities to me and opened my eyes to what is valuable and what isn’t out in the real world.

In a way, these experiences have given me a new perspective on how learning should be used – especially for people who are struggling to find their way in the world.

Here’s what I’ve learned about trying to become the absolute best at something:

It’s a Time Suck

No matter how you go about it, there’s no way to become world-class in anything meaningful in a timespan that isn’t measured in years. For truly difficult cognitive or physical skills, it could be a sizable chunk of your lifetime.

And this is assuming that you understand the learning process well enough to make progress as experience piles up.

For most people, this isn’t going to happen.

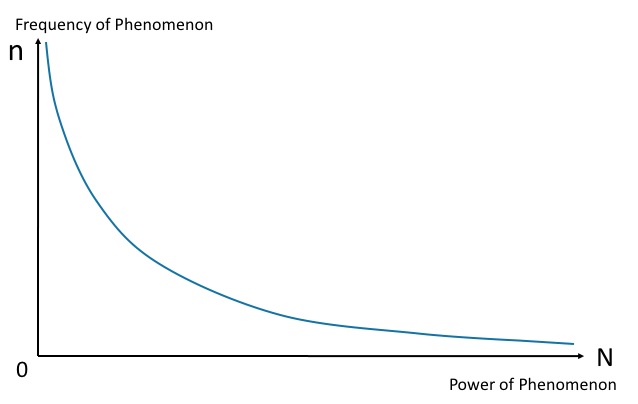

Why? There’s a real obstacle to long-term progression: the power law of practice (aka the law of diminishing returns).

What this means is that you’ll make large leaps and bounds early on in your learning, but, as you accumulate more skill and knowledge, your progress begins to slow down.

It looks like this:

Around the upper-intermediate/early-expert levels, the progress feels like it has slowed to a halt. This isn’t necessarily true, but it is easy to get discouraged because it’s so difficult to demonstrate meaningful learning at those stages.

Many people simply lose motivation here and stop. But plenty of others continue pushing forward, and still only make modest gains over long periods of time.

What’s even worse is that it’s extremely common for people to believe that sheer time is enough to make progress.

Here’s the unfiltered truth: Malcolm Gladwell is full of shit.

If you don’t practice correctly, if you don’t cater to the interaction between learning and memory, if you don’t grok the power law of learning at any level, it doesn’t matter if you throw 10,000 or 20,000 hours at your pursuit of mastery.

While it is true that some people manage to get very good at certain skills without explicit understanding of these concepts, it’s a common pattern that the best are the best because they’ve picked it up at some intuitive level.

There’s a Difference Between Skills and Abilities

The concepts of “skill” and “ability” often get lumped together, but we need to clear up the differences between the two before going forward (with definitions provided by Schmidt and Lee’s excellent book Motor Learning and Performance).

Skill is the capability to bring about an end result with maximum certainty, minimum energy, or minimum time; task proficiency that can be modified by practice.

If someone can consistently shoot a basketball well without expending much energy and got that way through copious amounts of practice, you can say they are skilled.

Ability is a stable, enduring, mainly genetically-defined trait that underlies skilled performance, is largely inherited, and is not modifiable by practice.

Abilities can be viewed as the basic “equipment” that enable skilled performance.

In plain English: skills are what you develop through practice, and abilities are what you are born with. Ability is talent.

The two are tightly coupled. For example, if you have excellent vision (an in-born ability that you can’t modify through practice) and you can use that to develop baseball-hitting skill by practicing a ton and utilizing your vision ability.

All skills have some level of ability that power how far you can take them. While you don’t have to have superb vision to hit a baseball and can get decent enough at it through practice, a competitor with superior vision and an identical practice program will end up better than you.

Talent Matters

It’s become almost taboo to say this now, but yes, talent is real. To say that talent doesn’t exist is to pretend that there aren’t genetic differences between people, which common experience can easily refute.

For example, if you believe that basketball players are endowed with height advantages that can’t be developed and yet think that the same types of differences don’t apply to cognitive ability, you should really take a moment to consider what you’re saying. The idea that genetic differences only exist in the physical realm is simply false.

Here’s where things get both interesting and a bit depressing: it’s nearly impossible to see how good someone can become just by looking at novice performance.

Why? Because A) the skills required for higher-level performance are not necessarily the same skills that are required when first starting out, and B) it takes time to adjust to the demands of a new task and use abilities to their fullest extent, which can take time even for high-level performers.

So you could feel like you have a knack for something from the get-go, only to find out that you simply can’t cut it at higher levels.

Likewise, you could be terrible at first and then turn into an expert performer later on. Either way, you’re going to be beholden to your abilities whenever you want to develop a skill.

This creates real frustration for people when they hit the intermediate skill levels.

Once they’ve started to exhaust the beginner gains on the left side of the diminishing returns curve, abilities start to become the real differentiator between performers and the probability of becoming “world-class” gets lower and lower.

It’s a Bet, Not Insurance

This is where I think it’s worth considering just how damaging the whole “just get extremely good at what you do” mantra. You can spend years of your life developing a skill, hoping to get to that world-class promised land, only to find that your abilities have denied you entry.

The abilities gap creates a situation where you need to be flat out lucky in terms of your genetics, otherwise you’re going to be stuck in the middle or rear of the pack.

This can be negated to a certain extent when there isn’t a large pool of competition, but once a skill set gets popular enough, abilities start to become more and more critical when it comes to determining winners and losers.

It might be possible to get there – skills can still develop to a high level with average abilities – but it could take far too long to happen.

You could spend (and many people have spent) an entire life trying to get there, only to find that they spent their prime developmental years aiming at a goal that simply can’t be accomplished.

This dynamic is especially nasty in the professional world. A person can try for years to be world-class in some in-demand skill, only to find themselves specialists in something that just isn’t that valuable anymore.

Economies and technologies move so quickly now that I think we’re going to start seeing this more and more from people who spend years in college and then realize what they learned in the classroom is obsolete.

The fundamental disconnect here is that world-class skill development is being sold as low-risk insurance against uncertainty, while it’s actually more like a high-risk wager.

A highly specialized, focused approach to skill development like that certainly can pay off in a big way. If you were a computer science geek back in the early days of the internet, there’s a good chance that you’re living an extremely comfortable life right now.

But even that was a big bet – computer science was not a mainstream discipline back then, and there weren’t millions of people jumping on the bandwagon like there are today. It was a sort of fringe subject for a long time, and not many people understood it.

If the internet and personal computing revolutions had not taken place, those CS people would likely be doing under-appreciated, underpaid work in academia instead of buying Ferraris.

It’s also worth mentioning that I advocate for a specialist approach over a generalist approach for activities like sports and other activities people view as formal, rule-bound “games” (such as chess, first-person shooters, etc.).

But that’s a whole other discussion that requires another deep dive into the context of skill development. For now, I’ll defer that discussion and focus on the larger “game” of economic success.

There’s a Better Way

Here’s an idea you should tattoo on the inside of your skull: if you’re losing the game you’re playing, you’re better off changing the game.

Sadly, the “world-class skills” crowd is more likely to simply admonish you for not trying hard enough and tell you to get yourself some discipline.

Don’t get me wrong, sometimes effort and discipline are lacking – and that should be fixed. But more often than not, it’s a matter of trying too hard to make something work that is destined to fail.

The answer, then, is to figure out what you can do other than burn through years of time and energy to figure out if you have the abilities you need to become world-class.

It’s not particularly complicated, but it does require some creativity.

Unlike the 10,000 hour rule, this isn’t some mindless blueprint you can follow and be 100% successful.

In fact, I’m not going to guarantee you that my ideas are going to guarantee anything – but I do think it could give you what you need to come up with some better solutions if you’re feeling stuck.

Don’t Be Someone Else’s Lego

Every skill that’s valuable is valuable specifically because it fits into a system of some kind.

An expert programmer is worth boatloads of money because he generates code that a company can sell in the form of digital products and services.

An expert baseball hitter is valuable because helps his team win, which raises prestige for the franchise (which in turn means more revenue from a variety of channels) – and so on.

Experts are cogs in other people’s machines. Their specialization often means that they’re not able to operate the whole machine – their vision is simply too narrow and their expertise doesn’t transfer to the system level. They are Lego blocks.

A real-life example of what I’m talking about is the case of Tracy Hall, a chemist who became the first person who grew a synthetic diamond according to a reproducible, verifiable and witnessed process, using a press of his own design.

GE made billions from his invention, and yet he was only given a $10 savings bond for his contribution!

This highlights an age-old problem, where brilliant experts become victims of their specialization when they can’t understand the larger economic system at work.

The most well-known example of this dynamic is the relationship between Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison (which has been covered millions of time, so I won’t go into detail here).

By trying to be the absolute best at something in the world, you are making yourself a Lego block. You’re not that useful on your own, but when placed with other Legos your value skyrockets – usually to someone else’s benefit.

Ask yourself: do you want to be a single Lego block, or do you want to build things with Legos? If you prefer the latter, you don’t need to be a world-class anything – you just need to build expertise in how to arrange those Legos.

If you take the time to figure out the systems that determine value for experts, the possibilities are nearly limitless.

Another way to think of all this is that it’s about developing a certain type of specialization that is not advocated for in schools or other public institutions.

That specialization requires a broader understanding of what levers matter in the larger games of life, and focusing on how you can manipulate those levers to your advantage.

You don’t need to be a genius or spend your whole life trying to master your backswing in isolation – you just need to keep your eyes open and watch how systems in the field evolve and operate.

What are systems? If you want an in-depth exploration of that, check out my previous writing on the subject.

The short answer, in this context at least, is organizations. A sports team. A business. An agency. Anything that operates by combining Legos together in ways that aren’t possible when Legos are working in isolation.

Bottom line: If you aren’t gifted enough to be an expert Lego block, stop trying to be an expert Lego block. Start building systems built out of Lego blocks.

Develop Skills to an Intermediate Level

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying never develop other skills. Aside from the fact that a life like that is going to be extremely boring, it’s not helpful for people who are looking for some entry into whatever world they want to enter.

I know that if I had not taken the time to become an intermediate-level programmer, I would not have the time or money to focus so heavily on 52 Aces.

If you’re lacking skills of any kind, you will need to develop some to get your foot in the door somewhere, make some money and start building things.

Apprenticeships should not be underestimated, either. No matter what domain you want to break into, you’ll save yourself a ton of time and frustration by working with someone who’s been in it for a long time.

The experience might even illustrate that you don’t want to be in that domain anymore and/or show you where to go next.

The answer here is focus on getting to the intermediate level as quickly as you can. To do that, you can use a system like the one I’ve laid out in my book, The Learning Factory.

By focusing on collecting skills and getting to the intermediate level – as opposed to focusing hard on a single skill – you’ll be setting yourself up for long-term success.

Not only are you going to have a variety of experiences and knowledge you can utilize to leverage yourself upward, that variety will also play well when it comes to building your systems.

Why? Because building systems is a skill that’s really more of a “metaskill” that’s built out of knowing how to accomplish lots of (often unrelated) tasks.

Building up a large repertoire of skills gets you to the point where you can see the whole picture, rather than focusing on your little corner of the machine.

Developing all those skills will expose you to the learning process for a variety of different formats, which in turn will make you a better learner.

By exploring a bunch of domains and learning skills from each of them, you’ll be more adaptable and capable of picking up new skills as needed.

Going through this process a bunch of times for a bunch of different skills makes you more nimble, more capable of adapting to the ever-changing world and, by extension, makes survival much easier.

This is why I always say that learning is the most valuable skill a person can develop. Life is nearly impossible if you can’t adapt, and learning is how we adapt to the world around us. If you don’t hone that skill, how can you possibly make it?

Psychological Relief

You know what is truly amazing about not trying to be come the absolute best? It’s a massive relief. While we love to idolize people at the top, we forget that those positions are more often than not outside of our reach.

And when that reality lands on us, it can be devastating – especially if many years of effort don’t pay off the way we wanted them to.

It also means that you don’t have to have all of your eggs in a single basket, which can be life-saving if things don’t work out the way you wanted them to.

For example, if you’re a star football player and spend your whole life getting ready for the professional leagues, what are you going to do if you sustain a career-ending injury?

If you’re well-versed in learning how to learn, it won’t be that much of a problem. Sure, it’ll be a big mental hit to watch your dream disappear, but you’ll be able to look around and figure out how to move forward.

It’s easy to look at the people at the top of their respective domains, who have long, prosperous careers and believe that we can emulate their success.

For a select few, this is possible. For everyone else, a better plan needs to be formulated to anticipate the inevitable plateau.

In many ways, it’s a relief to know that being “good enough” at something is alright. Rather than constantly carrying around shame about not being the absolute best and killing ourselves psychologically over it, we can move on and make the most with what we have.

I realize that this isn’t the feel-good message that many people want to hear. However, I’m not here to sell snake oil – I want to give you an honest appraisal of your odds out in the real world.

Most of us are not LeBron James or Joe Montana, and we have to find ways to survive in the absence of world-class skills and outlier abilities.

Win-Win

In a way, accepting this is really the only way to win. Consider the possibilities here:

- You truly have the abilities needed to develop world-class skills. Great, learning how to learn will allow you to reach the top faster than your competitors. Abilities + correct practice = domination.

- You’re around average when it comes to abilities and won’t be world-class at any one skill. Great, learning how to learn will allow you to fluidly adapt the to world around you and survive/thrive.

By focusing on learning how to learn and leveraging that skill to do whatever it is you want to do – whether it’s building systems or becoming the best at something else – you give yourself options.

Maybe you really are capable of being the best. Perhaps you were lucky enough to be born with superior abilities and the stars have aligned in such a way that your path to greatness is assured.

The rest of us need to accept just how long those odds are and come up with a better way forward.