Table of Contents

At the core of every life is a single, difficult question: should I learn more, or should I make the most of what I already know? This is known as “the exploration-exploitation dilemma” (aka “the exploration-exploitation tradeoff“), and it’s the most important problem you’ll ever face.

How this problem is handled is what differentiates a quality life from an impoverished life. How organizations manage it determines who wins or loses in competitive environments such as business and warfare. One could even argue that it’s at the very heart of evolution itself, meaning that this question filters down into even the most basic levels of existence.

This dilemma wreaks havoc in countless lives, but most people don’t know enough about the terrain of the problem itself to realize they’re failing to handle it in a constructive way.

Hopeful entrepreneurs go broke, promising careers end prematurely, and once-dominant companies disappear in a flash – all because this dilemma was not taken seriously.

If you care about having a good life, a good business or just want to create some clarity about how to make better decisions in a confusing world, then you must take this seriously.

I’m writing all of this not as some condescending expert who has figured it all out. Quite the opposite: I’ve spent most of my life getting this wrong, and then spending an inordinate amount of time trying to reorient myself in the right direction.

It’s been painful. You could say that what follows has been “written in blood,” as my primary hope here is that someone else who is at an earlier stage of life can absorb what I’m communicating and avoid many of the mistakes I’ve made in the past.

Let’s also be clear about one thing right from the get-go: there isn’t a single, optimal solution to this problem. You’ll never “master” it to the point where you don’t make mistakes. All you can do is recognize the problem and do your best to balance the conflicting forces in a more intelligent fashion.

The Basics

You can start to deconstruct how this all works by breaking down the name itself: the exploration-exploitation dilemma. We’re discussing a dilemma/tradeoff and it’s a balancing act between two different activities.

Exploration is any activity that involves gathering new information, going outside of your current knowledge base and, most importantly, changing behavior in a way that has an unknown payoff on the horizon.

In more practical language, exploration is experimenting, trying new things, making educated guesses and throwing yourself into the world without knowing what the outcome will be. If you ever find yourself saying “Let’s see what happens when I do this,” then you’re exploring.

Exploitation, on the other hand, is taking advantage of what you already know and utilizing the “tried and true” path to known payoffs. Exploiting is more or less doing what you’re familiar and comfortable with, and generally putting yourself in situations where you know what the outcome will be most (if not all) of the time.

These are not difficult concepts to wrap your mind around – one revolves around trying new things, while the other is all about doing what you’re already comfortable with. These are ideas that most people understand at an intuitive level.

Consider a toy example: picking a place to eat. If you decide to go back to the same Chinese place you’ve been to a million times, you’re exploiting. If you’re feeling a little more adventurous and pick a place you’ve never been, you’re exploring.

You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to come up with ideas about how to handle problems like picking a restaurant. Most people find simple, easy ways to handle low-impact choices like this. Where things get challenging is when you expand time horizons, introduce a healthy dose of uncertainty and put real stakes on the table.

Multi-Armed Bandits

The most famous formulation of the exploration-exploitation dilemma is what’s called The Multi-Armed Bandit Problem. It’s an academic concept, and it comes with some academic assumptions – but it’s helpful for thinking about everything we’re going to cover here, so it’s worth a simple overview.

Picture yourself in a large room filled with thousands of slot machines (this is where the name of the problem comes from, as slot machines are often called “one-armed bandits”). Each one has a defined payoff for each wager you put into it, but you have no idea what those payoffs are.

You have a limited amount of money which you can put into the machines, so it’s up to you to figure out the optimal use of that money. You also can’t go back to a previous machine once you’ve moved on to the next one.

Let’s say that you discover a machine that has a small, but predictable payoff pattern. You put in one dollar, and it gives you back one dollar and two cents. This isn’t a huge payoff, but you keep pulling the arm of the slot machine and realize that it will consistently provide that two cent payoff as long as you put a dollar in.

Should you just keep plugging away at that two cent return, or should you try to discover a bigger payday in one of the other machines? After all, there might be a machine that gives you twenty-five cents, or even another dollar, each time you pull the arm.

But many other machines will give you nothing, or give you payoffs that are so infrequent that it’s a net loss even with larger individual wins.

Remember: you can’t go back to a winning machine once you decide to move on, so every time you change it’s a gamble. You could spend a lot of time and money trying to find another winning machine, meaning that even a small two cent payoff might be worth holding onto if you can’t risk very much.

This is the heart of the exploration-exploitation dilemma. Banking on that two cent return is exploiting, and foregoing it is exploring. Balancing known payoffs against opportunity costs that arise from not exploring is a great way to start thinking about all of this.

The multi-armed bandit model is used in a variety of fields, such as clinical trials and conversion rate optimization.

But, like I said before, it’s an academic formulation. The fact that there are known, fixed payoffs is particularly misleading if you want to solve real-world problems. It’s more useful to transfer all of this into larger, more complex scenarios you’re likely to face.

As a side note, one of my favorite anecdotes about this problem comes from the Wikipedia page (which I recommend reading):

Originally considered by Allied scientists in World War II, [the multi-armed bandit problem] proved so intractable that, according to Peter Whittle, the problem was proposed to be dropped over Germany so that German scientists could also waste their time on it.

A Natural Place to Begin: Your Life

A natural framework for understanding the exploration-exploitation dilemma is how most of us treat learning throughout the various stages of our own lives, which is often informed by environmental and societal factors. I use a set of simplified life patterns to think about how most people in this world tend to react to the exploration-exploitation dilemma.

The general idea for most people living in stable, safe environments is that their early childhood should revolve around play and care-free experimentation. In other words, kids who grow up in these kinds of environments are encouraged to spend the bulk of their time in “exploration” mode.

As time goes on, these children are expected to start learning specific types of knowledge – generally passed down through institutions such as schools – that will be useful to them later in life. Kids are taught subjects such as English or math so that they can think and communicate effectively as adults and become skilled professionals.

After this period of knowledge accumulation (aka exploration), young people are told that it’s time to transition to patterns of exploitation. They get jobs and embark on careers that utilize everything they picked up ahead of time.

Time in this pathway erodes exploration away more and more over time. Relationships are formed and consolidated, preferences become solidified, and everyday routines blur large blocks of time together.

Eventually, these people are told that their exploitation will end sometime around the age of sixty-five, and they can then safely retire to focus only on what they love to do with their time (in other words, pure exploitation).

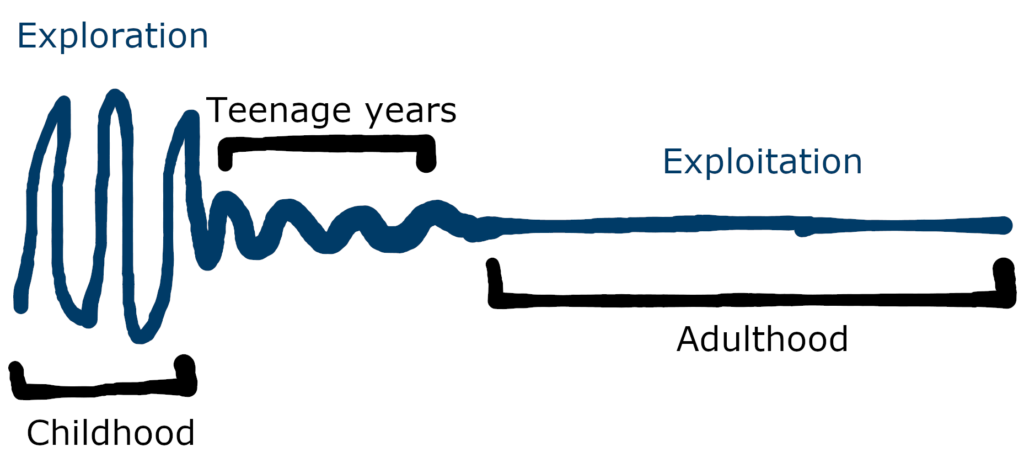

If we were to draw out a simple illustration to demonstrate the overall structure of this explore-exploit pattern, it’d look something like this:

For the sake of clarity: the large zig-zags represent variation and exploratory behavior, while narrower zig-zags and straight lines represent predictable, exploitative behavior.

I like to call this the Standard Pattern. This is the blueprint that most well-to-do, middle-class people are raised to believe in (at least in Western, developed countries). Childhood is for exploration and freedom, the teenage years act as a point of decreasing variability, while adulthood is for exploitation and focus.

It sounds reasonable on the surface. The Standard Pattern has worked well to produce a decent life for a nontrivial number of people. But there are a variety of serious problems with this path as well.

For one, the Standard Pattern treats exploration as some kind of silly “phase” that adults grow out of and eventually discard entirely – except for simple choices like where to take your next vacation or what brand of car to purchase. Idle wandering is treated as an immature waste of time that can only be indulged in by the very young or the very stupid.

The Standard Pattern, in other words, views variety as the enemy. It boils down life into a simple equation of utility, and robs everyone within it of any sense of curiosity for the sake of taking the safe route.

It’s a way of life designed for those who have only a passing interest in taking any kind of risk. People who believe wholeheartedly in this way of living are by definition pro-establishment, pro-stability types who will never step outside of what’s comfortable to find out what else the world has to offer them.

You could say that the Standard Pattern generates a sort of tragedy for those who live it. They can be happy, but it’s only because they remain ignorant of the possibilities that they’re missing due to their lack of curiosity.

These people don’t want to fail, so they don’t put themselves in a position to fail. Or if they do, it’s not substantial or frequent enough to matter.

The Standard Pattern also just doesn’t work for people who grew up in an unstable, high-risk environment (such as developing countries). In these types of situations, the scenario tends to play out a lot differently.

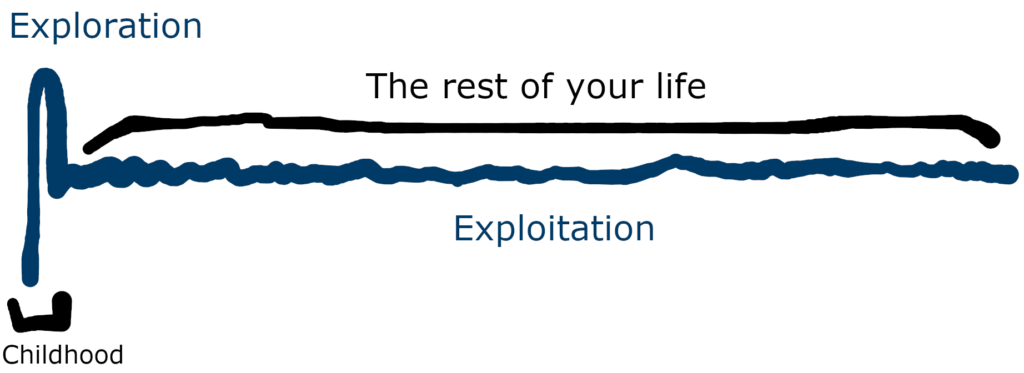

What we see instead is what I call the Scarcity Pattern:

Basically, you’re given a minimal amount of time (mostly as a child) to explore and enjoy yourself, then you’re expected to take the safest, most predictable pattern possible.

People who live their lives this way rarely do it out of choice. They have limited options and resources to work with, and as a result have to forego anything resembling pleasure in order to survive in an intense, competitive environment.

Consider a person born into a rural background in a country like India whose parents want something better for their child. The parents have spent their whole lives breaking their backs doing hard labor (a sort of Scarcity Pattern of its own, since farming is one of the most well-tread exploit patterns in the world) and want to see the whole family lifted out of poverty through a different path.

So they raise their children to be world-class students in order to pave the way for them to become doctors, lawyers or engineers. It doesn’t really matter if the child enjoys, or is even good at, the subjects required to make it in one of these fields – what matters is the safe, predictable payoffs that come from breaking into them.

The Scarcity Pattern is suboptimal for human happiness, but it’s a pragmatic pathway that many (at a global level, most) people are forced into. While there are a variety of problems with the Standard Pattern, the Scarcity Pattern is one of the greatest sources of wasted potential on the planet.

People are forced into a path purely because it’s an unreasonable risk for them to even consider exploring. If the risk of exploration is homelessness and/or starvation, then exploitation is the only option.

But the cruel irony of the Scarcity Pattern is that it locks people into a suboptimal path that they can’t escape from without an incredible amount of luck. If you are forced to stick with the same, predictable payoffs out of necessity, then you’ll never be able to look around for a path that is much more financially and/or personally rewarding.

You just sort of do what you have to do until you die. It’s a sad story, and far too many people are living it. If we can get more people out of the Scarcity Pattern, we will do much to advance the quality of life for everyone on earth.

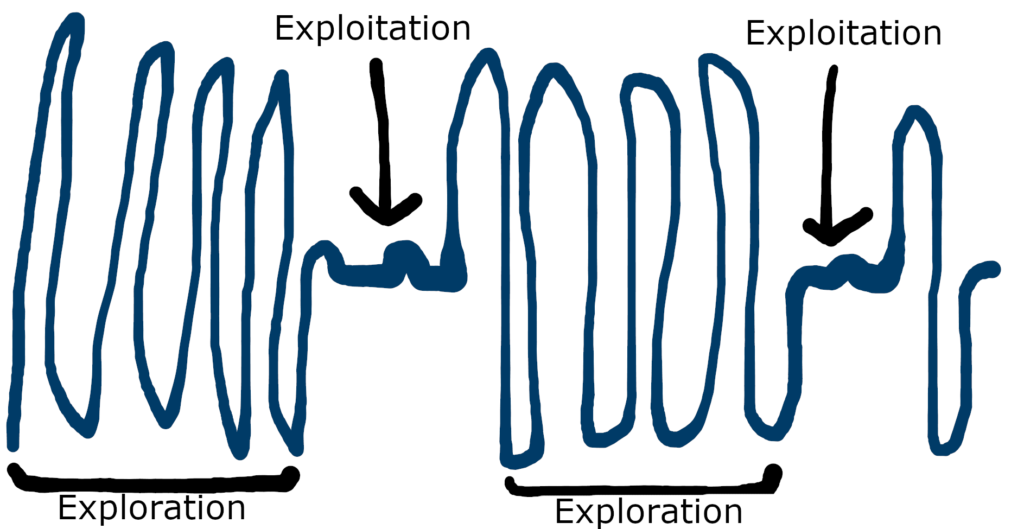

On the opposite side of the spectrum, there is what I refer to as the Luxury Pattern.

This is a pretty rare pattern, because it’s mostly exploration – and exploration is expensive. People who live like this tend to be those who are born into situations where money, time and other valuable resources are abundant. You’ll notice that there aren’t any life stages attached to this graph, and that’s because it’s a repeating cycle.

Think of the rich trust fund kid who never seems to have a cohesive pattern of behavior, but never seems to run into serious trouble because of his family’s money. He can spend all of his time wandering around, trying out all that the world has to offer, all while making copious mistakes along the way.

Consequences aren’t a major factor for those living in the Luxury Pattern. If they start a business and it blows up, they can shrug their shoulders and walk away. The same can be said for all of their other life choices involving responsibility.

You’ll notice in this (beautiful masterpiece) of a graph that there are short periods of exploitation. These represent those brief intervals where those who can afford to explore all the time give focus a shot. This is usually brief, as exploiting is usually less stimulating if there aren’t survival-level stakes on the table.

I knew a guy who fit this description pretty well. He was born into money, was educated via world-class institutions in places like Switzerland, and otherwise had all the advantages you could ask for provided to him by his wealthy and successful father.

Once his father died and left him a sizable inheritance that guaranteed a high-class income for life, he decided he was done with the whole “work” thing and started living the life of a pure explorer. He spent most of his time traveling, smoking copious amounts of weed and trying his hand at various business ventures.

Every time he’d give business a shot, he’d fail. It wasn’t because he lacked the funds or didn’t understand markets. It was simply because he didn’t like the idea of focusing too hard on anything for more than a few months at a time. He preferred to get stoned, make terrible techno music in his in-home studio and jump on random flights to faraway places.

His life fit the Luxury Pattern almost to a tee, and even though I haven’t spoken to him in years, I have no doubt he’s still in it.

Academics tend to fall into this category as well, although the Luxury Pattern kicks in a little later (some might be born into a different pattern and end up here). They’re a sort of paid explorer, and they aren’t expected to apply their knowledge to anything beyond the papers they publish.

While this might seem like the Ultimate Pattern in many people’s eyes, it is in fact a pretty damaging way of living as well. It is certainly better to not be stuck in the Scarcity Pattern, but if all you never do anything except explore then your life tends to be pretty vapid.

Consider how many people who come from generational wealth are bored, depressed characters since they’re almost never given a life path that involves meaningful risk or personal development (which tends to come as a result of absorbing real losses). Many resort to a party-hopping lifestyle that revolves around trying to discover something, anything, that will make them feel alive.

My stoner-traveller-musician acquaintance led a pretty empty existence. He did what he did because he needed stimulation, and he never had to worry about going broke. If he failed (and he always did), he could just jump on a plane and disappear before any angry investors could take him to court. His inner life was impoverished, to say the least.

The Costs & Benefits of Failure

What separates each of these patterns is what happens if you don’t make the right choices. For those who are stuck in the Scarcity Pattern, failure is catastrophic.

To use the example of the rural farming family in India, if that child fails to pass those important exams and make it to the world of white-collar work, the consequences are substantial. It means that another generation of that family will in all likelihood be stuck in the same miserable pattern as the previous ones.

For those who are in the Luxury Pattern, failure doesn’t have a meaningful impact. The rich playboy can do whatever he wants (even break laws, in many cases) without having to deal with the downsides of those behaviors.

And people in Standard Pattern lifestyles face some risk when it comes to failure, but they tend to not take enough chances for it to be meaningful. They prefer a steady paycheck over the uncertainty and possible instability of entrepreneurship, for example.

It’s worth asking: what is the utility of failure? Failure is a valuable element of reality, as it informs creatures of all kinds about the accuracy of their models of the world.

When a relationship fails, it means that two people held incorrect beliefs about each other and the realities of interaction showed both parties how they were wrong. Businesses often fail because founders have over-optimistic beliefs about the prospects of making money with their idea.

In other words, failure is critical for learning – and if you don’t have a full reservoir of failure experience to inform your beliefs, you’re going to get into trouble.

Each of these patterns I’ve laid out includes some pathologies related to failure:

-

The Luxury Pattern shields those within it from the consequences of failure, so they never learn to adjust (since they sense, correctly in many cases, that they don’t have to). This is why many rich people, despite their resources, are not particularly intelligent or rational.

-

The Scarcity Pattern makes failure such a traumatizing event that its inhabitants are forced, out of necessity, to do everything they can to avoid it. What this means, in a practical sense, is that they only ever learn in very specific, narrow ways that apply to their current exploitation routines – which ensures they stay where they are. If you’ve ever talked to a life-long inhabitant of a poverty-stricken area, you’ll notice that they tend to be very smart about their direct environment, and not particularly interested in or knowledgeable of the world beyond (again, there are many exceptions to this and I don’t mean to paint every poor person as a know-nothing).

- The Standard Pattern is a societal force that allows room for failure, but discourages it in favor of following a safe, risk-averse lifestyle. Because those in the Standard Pattern tend to make their living from steady paychecks, they end up in a kind of hypnosis where they overestimate the risk of behavioral deviation and cling to safety. In other words, they could fail and be okay in many cases, but they’ve been led to believe that such behavior is unacceptable.

The Luxury and Scarcity patterns represent extremes: over-exploring means you never fail because you’re too busy probing to ever bother trying anything, and over-exploiting means you never fail because you’re too scared to try. The Standard Pattern leaves the potential for failure open, but it is rarely taken advantage of (at least to the degree that those inside it could get away with).

One element that’s worth mentioning here is that, despite the various patterns we’re often forced to inhabit, children tend to be very good at exploring. Even with overbearing parents, kids often find ways to explore in spite of it all and thus end up running their own failure-prone experiments.

Kids, without any kind of instruction, tend to do what we should all be doing as adults: failing early and often. It’s a truism in the world of expertise that those who play around, discover the boundaries and generally try new things at the beginning stages of learning end up as the best long-term performers.

Why? Because if you’re failing a lot, then you’re exploring the limits of a system and discovering what various inputs do without having someone else’s inherited knowledge cloud your thinking. If you only follow the paths others have paved and never explore on your own, then you’ll never have a different perspective that’s worth anything.

Another thing that kids seem to intuitively understand is that the costs of failure are often much less severe than we think. Kids are much less concerned with status, prestige and other societal constructs and are thus more willing to try things just for the sake of trying them.

An example I like to use is tapping in martial arts. If you’re training and someone catches you in a submission that forces you to tap, who cares? The reality is that nobody, aside from you, will even think very much about it.

But full-grown adults will lose their minds over meaningless losses in the gym because they have lost that child-like ability to understand how such failures are both pointless (from an overall importance perspective) and beneficial (from a learning perspective) in the long-run.

The key then becomes finding constructive ways to fail and learn outside of the short, contained stages of childhood.

Some Principles We Can Now Extract

Before moving forward, let me just posit that a person can start in one pattern, and then shift into another pattern (even multiple jumps are possible). There are also exceptions that need to be taken into account.

For example, many people born into what looks like a Luxury Pattern are forced into a weird sort of Scarcity Pattern when their rich family tells them they must go to certain schools, work for the family business, etc. or else they get nothing.

On the flip side, a hobo might be living in a weird sort of Luxury Pattern: he’s spending the bulk of his time traveling on trains and only working in sporadic bursts as a way to support that lifestyle. Even though this person might be, on the surface, someone you’d assume to be part of a Scarcity Pattern, their ability to live such a free lifestyle flies in the face of the stereotypical model.

These are just general models used to illustrate some important principles of the exploration-exploitation dilemma. Models are always wrong in some ways, and mine are no different in that respect.

With all that in mind, here’s what we can glean so far:

Don’t explore if the costs of failure are too high…

Being able to go outside the boundaries of known patterns in order to discover new payoffs is reserved for people who can afford to do so. If you can’t afford to make mistakes, then exploration isn’t an option.

The best description of this dynamic I’ve ever heard was “don’t dance through a minefield if there’s a clear path already.”

…But be aware that there is a cost to not exploring

Something that doesn’t get brought up enough in discussions about this dilemma is that there are serious downsides to not exploring. If you don’t go outside of what’s familiar to you, then (unless you stumbled across the best personal and financial payoffs by sheer luck) chances are very high that you’re missing out on a life path that would make you much better off.

It’s worth considering if the costs of failure are as great as you think they are right now. In many cases, the costs of failure are imaginary (or at least much less impactful than you think). Is this true for you?

I’ve made a point of regularly asking myself if failing with what I’m working on is as big of a deal as I think it is, and I’ve found that my estimates are wrong most of the time.

Fail early, fail often

It’s been said many times before, but it is true that you need to fail a lot early on. The idea here is that you want to find the boundaries and discover what inputs to a system do – in your own way.

Failing to fail, so to speak, is a serious problem that should (and in most cases can) be avoided.

There’s an old saying from Chess that does a good job of encapsulating this whole concept: lose your first fifty games as fast as possible. The idea is that you can speed up your learning and begin developing your game by playing (and losing to) better players as often as you can early on.

Exploring has long-term payoffs…

Checking out what the world has to offer is a practice that, more often than not, ends in disappointment. The majority of your time will be spent hitting dead ends (failing). But if you keep at it long enough, you’ll discover things that generate long-term, compounding payoffs.

…While exploitation has short-term payoffs

In most cases, exploiting existing knowledge will generate predictable, tangible benefits – which is why we tend to lean so heavily towards exploitation. Even if the result is suboptimal, we don’t have to deal with the dread of uncertainty. The problem is that your long-term results will suffer if all you do is exploit.

There are costs to doing too much of either

If you spend all your time exploring, you won’t ever reap the benefits of the knowledge you’ve picked up. By default, exploring is only beneficial if you use what you’ve learned in an exploitative activity at some point. On the flip side, exploiting too much ends up generating suboptimal long-term returns because you never bother looking for better pathways.

Games The Dilemma Plays

One of the most insidious pieces of this puzzle is that we’re naturally wired to take suboptimal paths when dealing with the exploration-exploitation dilemma. It’s as if evolution has played some kind of cruel trick on us by wiring our brains to respond to the wrong incentives.

The key is that exploitation tends to reassure us and, in many cases, generates pleasure. When payoffs are known, we feel safer and we become less likely to deviate away from pathways that are less certain but potentially better for us.

If you’re overweight, it’s likely because you’ve become accustomed to eating familiar (bad) food in large quantities, which feels good in the short-term.

Pizza and ice cream both kick off pleasurable responses for us, and exploiting your taste for those things over and over again feels very nice over short periods of time.

But exploiting those tastes and eating patterns can kill you. What makes dieting challenging then is often not only about breaking established habits, it’s about exploring pathways where you don’t know payoff magnitudes (total potential fat loss) or timespans (how long it’ll take you to get to your healthy weight).

Losing weight requires a large amount of exploratory behavior because everybody has different goals and energy requirements. While the principles are universal (eat at a caloric deficit and exercise regularly), these need to be refined for individual situations.

A bodybuilder looking to burn a few extra pounds of fat before a competition has very different needs from an overweight knowledge worker who has never exercised in his life. Both have different amounts of exploring and exploiting to do in order to reach their different goals. It’ll take time and, most importantly, failure in order to reach the endpoints they desire.

This is the core challenge in weight loss and many other habit-changing activities – everything else is pretty easy in comparison.

Piggybacking on the previous concept, it’s worth remembering that, within the exploration-exploitation dilemma, exploiting is always easier. Although that known path may not be much fun (working a job you dislike for a paycheck that keeps your lights on, for example), it’s much simpler to just keep doing the same things than to explore other pathways and, in turn, take on risks.

Exploiting is comfortable, and as such many people find themselves doing the same suboptimal things over and over again rather than face the music and get their failures over with.

A real-world example would be a marriage where both partners are miserable and yet unwilling to take steps to either rectify the situation or just admit that it isn’t fixable and move on.

In this case, exploration would involve some very painful, uncertain choices. If they’re older they’ll probably have a lot of anxiety about whether they’ll meet another person or if this decision will damn them to a lonely end-of-life scenario.

It’s often the case that they’d rather just gut out a bad relationship than take on those risks (which is its own kind of slow-motion tragedy).

Another way to frame this is to approach it from the other direction: exploration is painful and uncertain.

We are programmed by both evolution and society to stay away from anything that’s too painful or uncertain. To adopt an exploratory mindset means you have to volunteer yourself for lots of pain, uncertainty and failure.

Needless to say, not many people are equipped to do this for sustained periods of time.

This is another reason why exploration is such a luxury: if you have the resources to explore at will, you can shield yourself from the high levels of pain that normally accompany such behaviors.

Rich people tend to have lots of fake friends, for example, and it’s largely because they can afford to drop those they don’t like at will. They aren’t leaning on them for anything other than stimulation in many cases, so it doesn’t matter if a friend drops off the radar.

People within poorer communities, on the other hand, rely on each other much more and are much less likely to deviate from relationships they’ve had for a long time. Family and community bonds matter when you can’t afford to lose them.

There is a bit of a paradox at the heart of exploration, though: while it is painful, it is also much more exciting. People can get addicted to exploration because of the thrills that come with discovering new things, and this leads to Luxury Pattern-type lifestyles where meaningful, exploitative action is never taken.

Life-Stage Considerations

Managing the dilemma tends to be most impacted by whatever stage of life you’re in (this applies to organizations as well, which we’ll discuss later).

To understand what I mean, consider what you might do if you knew that tomorrow you were going to die. Would you go try to make a bunch of new friends at some random bar you’ve never visited, watch movies you’ve never seen, eat food you’ve never tasted?

The most likely answer to all of that is “no.” You’d want to spend your last twenty-four hours with people you care about, doing things that bring you the maximum amount of pleasure.

To summarize: if you’re at the end of your life, you should focus exclusively on exploitation. The long-term nature of exploratory payoffs aren’t worth anything to someone who won’t be alive to take advantage of them.

On the other hand, it makes sense for those at earlier stages of life to spend a decent amount of time exploring. With longer time horizons, the long-term payoffs from exploration create much better outcomes than a purely exploitative approach (which is by its very nature short-term).

It wouldn’t make sense to tell a kid not to read books or go to school, for example, since the expectation is that their long-term prospects will be improved by education. The only case where it makes any kind of sense to tell a kid not to is so they can contribute their labor (a Scarcity Pattern that is still seen in the developing world).

The Patterns in Organizations

The patterns from the individual section apply here as well, but there are some distinct ways organizations need to view this problem that don’t necessarily apply to individuals.

I think businesses are the best organizations for this kind of analysis, as there are very clear goals and metrics (such as profitability and market share) we can use for gauging whether a business is making good decisions or not. This is not always the case with organizations in fields such as politics, where goals can be more challenging to identify or interpret.

At the very beginning of a company, there tends to be either a single founder or couple of co-founders. Their job is simple: discover a way to make money. In other words, their first priority is to explore.

This sounds simple, but a surprising number of businesses get it wrong and collapse before they ever get off the ground.

Let’s use an imaginary company called ABC Corp as a basis for building understanding. We’ll say that ABC was started by one founder, Joe, and he has no idea what he’s doing (which is pretty standard as far as founders go – I’m speaking from experience here).

There are a variety of traps that Joe can fall into that are all related to not understanding the exploration-exploitation dilemma, or at least not acting in a way that is congruent with the realities of it.

The first is to assume that the Luxury Pattern is the best way to run a business. People who make this mistake tend to spend all their time focusing inward, thinking about their product, reading books, watching TED talks, and otherwise treating their business like one giant thought experiment.

There are short exploit intervals involved where some work gets done, but the effort is never sustained long enough to amount to much. Instead, the lure of exploration keeps calling the founder(s) back, keeping them safe and protected inside their own minds.

In ABC’s case, Bob has spent the last year working on his product without attempting to sell or market it to anyone. He’s convinced that the model he has in his head about what people want is sufficient, and this means his path to success revolves around gathering more information.

Bob’s trap is particularly insidious because, by committing time, resources and social “status points” to his Luxury Pattern endeavor, he’s creating his own kind of demented sunk cost fallacy. He’s spent a year working on this product, and it would be far too devastating for his ego to go out into the market and discover that nobody wants it.

To some degree, Bob has to have gathered some information from the external world that might invalidate his idea. He might have mentioned it at a networking event or told friends about it, only to receive negative or (even worse) indifferent responses.

So he spends his time living in his own head, filling his days with visions of success that will come as a result of his brilliant information-gathering strategies.

If you’ve never spent time around entrepreneurs, this might sound far-fetched. But it’s so common that there’s even a term for those who continue living in the Luxury Pattern forever: wantrepreneurs.

The problem is that Bob has a fundamental misunderstanding of what patterns are appropriate for the life-stage of ABC. The Luxury Pattern does work in some instances. Google’s modern ethos of encouraging exploratory behavior (and even opening up a secret exploration-focused wing, Google X) is a sort of Luxury Pattern, and you can see something similar in very successful companies.

Why? Because exploration is a luxury, and if you have billions of dollars to spend, you should indulge in that luxury. Even if 99% of experiments fail, the 1% that are successful will be such a big deal that all the costs won’t matter in the long run. Venture capital runs on this same formula: invest tons of exploratory dollars in a variety of companies in the hope that one pays off big (at which point they can exploit by dumping more money into it).

For Bob-level entrepreneurs though, this is a terrible idea. Instead, it’s a much better idea for ABC to adopt something along the lines of the Scarcity Pattern at the beginning.

The way Bob could turn everything around is pretty simple: he can do a little bit of exploration by cold calling, emailing, and otherwise getting in front of people he doesn’t know (this is important, as data from friends and family tends to be deceiving). As he does this, he asks each person if they’ll give him money for this thing he wants to build.

The algorithm from here is pretty simple: once he gets a critical mass of committed buyers, he switches into a near-pure exploitation mode by focusing on delivering what those buyers want. This is how Bob can keep the lights on, grow and, at the end of the day, proclaim himself a real entrepreneur (and not a wantrepreneur) with real customers.

I’ll go as far as saying that the Scarcity Pattern is the superior pattern for every early stage company. Most people think their company needs to innovate or do something else that’s product-centric, when the reality is that most companies just need more customers.

This is why, in a capitalist world, it makes sense to copy whatever’s already successful and it’s often a mistake to enter a market as an innovative leader. Other, more efficient companies, will just wait for the innovator to prove that their product is worth something, then enter later and steal their market share (a well-known problem called the innovator’s dilemma). It’s a much more reliable, risk-averse strategy to be a copycat when you’re starting out.

Problems begin to appear later on, when a company has exploited its way to a profitable position within a large marketplace. If they stick with the Scarcity Pattern, then they’ll never explore enough to catch on to trends in the market that can take them out of their leading position.

That pattern’s effectiveness begins to turn into a liability and the top dog gets knocked off its perch.

There’s even a term for what happens internally at organizations like this: the competency trap. The general idea is that competency in suboptimal, but profitable, organizational behavior makes exploring so unrewarding that companies stop engaging in it.

Picture a company that has expert skills in manufacturing typewriters at the dawn of the computer age. Everything in their factory is geared towards making the world’s best typewriters, and making changes to the assembly line would be so costly, and would cause so many unprofitable slowdowns, that the company’s managers (who are incentivized to think short-term) never bother changing anything.

Then the computer comes along and makes the entire organization obsolete. It’s all because they were stuck in a competency trap and didn’t recognize a need for exploration until it was too late.

Many companies follow their own kind of Standard Pattern, where there’s lots of thrashing at the beginning (when the founders are looking for cash flows), followed by some stabilization (growth and scaling up), then a flat line of exploitation until the company dies.

It’s not a surprise that very few companies end up lasting more than a handful of years when most are operating this way. Competency traps and other maladaptive responses to uncertainty ensure their long-term demise.

The Dilemma in Competition

Generally speaking, the dilemma is something that applies most to situations that can be labelled as “competition” or “conflict” – hence the connection to business.

A constructive way to think about this, then, is to transpose the dilemma onto the various competitive games we play with each other. The patterns still apply, and there are some special considerations for anyone who wants to “play to win.”

Competitors are obsessed with ways to get an “edge” over their opponents. Discovering those edges is, as a result, one of the most focused-on aspects of competitive development. Coaches in every sport and game imaginable have been contemplating the best ways to defeat the opposition with clever strategies since people started playing games.

But the way most people think about this revolves around specific strategies and tactics within the game itself. I would argue that the more important consideration is figuring out when to engage in exploration or exploitation, and how to identify the appropriate moments for switching.

At the very beginning of a competitor’s career, they should be taking the child-like approach of probing around as much as possible – breaking the game, as we discussed before. This will involve quite a bit of failure and, in most cases, competitive disappointment. While this might not feel great, it is the correct pathway for anyone who wants to be a long-term winner.

This dynamic is well understood by most competitors: you start out exploratory, then start to narrow down into exploitative patterns as you gain more information through time and experience. But what tends to vex most people is the transition from intermediate to expert.

My argument here is that the difficulty people face is that they tend to get trapped in some kind of suboptimal exploration-exploitation pattern in the middle, and end up wasting a lot of time floundering because they don’t understand why they’re stuck.

A big piece of the problem is the life-stage requirements we went over earlier. As a competitor, it makes sense to be exploratory early, but as time goes on it does indeed make sense to become a high-level exploiter. And yet this creates a nasty competency trap – if you become too specialized, you become predictable, and being predictable is the number one anti-pattern in competition.

What’s a competitor to do? Well, the first thing is to understand these two fundamental principles:

-

Exploitation is for survival. If your goal is to keep your head above water and not finish last, then you should be exploiting. In other words, exploiting is for not losing.

- Some exploration is needed for excellence. What separates the people at the very top from those in the middle is the constant desire to keep exploring new spaces and adapting with new patterns. Exploration then is for winning.

Think about the difference between the person living in a Scarcity Pattern versus a person living in a Standard Pattern. Scarcity Patterns are designed to ensure survival – and that’s it. Anything else is not a consideration, hence the lack of exploration.

The Standard Pattern isn’t exactly optimal, but it does do a good job of putting a person in a superior position when compared to those in the Scarcity Pattern. Why? Because there are exploratory periods that open up at least a few better pathways.

We’ll discuss the near-optimal pathway in a minute, but the idea is pretty simple to distill: if you never explore, you’ll never live on your own terms. You’ll always be stuck in the same, predictable patterns and, barring some extreme luck, will spend the bulk of your life in a holding pattern.

The big question for a competitor then becomes: what are you trying to do? High-stakes competition makes people more risk-averse, so they tend to focus on exploitation too much. This generates short-term rewards, but paradoxically creates a situation where that exploitative pattern becomes the key to their defeat.

When you’re on top, you can’t afford to be predictable. Everyone is watching you and studying your behavior, looking for patterns that can be used against you. This is why the very best competitors across different fields always keep at least some exploration in their practice routines.

An additional question tends to arise here: how do you identify when it’s time to be more exploratory or exploitative? Dealing with this is not as hard as you might think (at least from a conceptual standpoint).

It boils down to always finding ways to put yourself in a position to perform at a “mediocre” level in practice. The reason for this is that plateaus – those seemingly endless periods of non-progress – tend to be the most difficult, demotivating part of any learning process.

Plateaus often boil down to a practice or competition routine that revolves around winning all the time and never putting yourself in a position to fail (which in turn means never learning anything new). This makes you predictable even in practice, so you end up in a plateau because everyone you train with knows how to shut your game down.

A simple way to break down what I mean is that you can get caught in a competency trap by becoming addicted to winning. This might sound crazy to die-hard competitors, but the truth is that winning all the time creates losses in the long-term.

Practice isn’t about confirming how good you are. Practice should be about screwing up, learning and getting your failures out of the way in situations where it doesn’t matter. Some of the best competitors in the world will put themselves in losing positions in practice on purpose, so that they can be prepared for a wider pattern of contingencies in real competition.

Most people struggle with this. It feels good to win, and utilizing a high level of expertise is an addictive drug all on its own. Remember what we talked about earlier: exploitation is pleasurable. And it’s this seductive, pleasurable feeling that tends to sink the best competitors in the long run.

That covers practice – what about competition itself? Well, that’s a slightly different story. When you’re in the heat of competition, exploration will pretty much guarantee a loss. Even though it might generate some kind of novelty that in rare cases will put you over the finish line, more often than not the lack of experience with that specific pathway will end up taking the win away from you.

This is why failure and exploration in practice is so important: it gives you the situational information you need to be adaptable in a wide variety of competitive environments. If you’ve lost a ton of times and learned a lesson from each loss, then you can know what to do (or not to do) when faced with difficult, loss-inducing situations.

At the end of the day, this is what you can say about the dilemma in competition:

- Exploiting is for survival, exploring breeds long-term excellence.

- You should always set aside some practice effort for exploration, no matter what stage of development you’re in.

- Getting addicted to winning in practice will kill you in the long run because it will prevent adequate exploration.

- The day of competition calls for exploitation, which means you better have done some constructive exploring leading up to it.

- Plateaus can be defeated by constantly forcing yourself to be “mediocre” in practice.

The Quality Pattern

This brings us to the pattern that I think does the best job of handling the exploration-exploitation dilemma: The Quality Pattern.

With the Quality Pattern, the general idea is that you want to explore a lot early on (again, exploring boundaries, breaking the game, etc.), and then start to narrow over time. But the big difference here is that, unlike the Standard Pattern, you keep exploration as a priority for the rest of your life.

There are bound to be periods of exploitation, and that’s a good thing. As I mentioned before, exploiting and exploring need to go together to work. If you don’t exploit using what you’ve picked up during periods of exploration, then your exploration was useless.

So a well-lived life, a well-run competition preparation and a finely tuned organization all utilize the Quality Pattern of exploring forever, but incorporating that exploration into exploitation on a regular basis.

A good rule of thumb, especially once you’ve hit the intermediate-to-expert levels, is to set aside a minimum of 20% of your available resources for exploration.

Even small amounts of exploration, mixed with well-oiled exploitation processes, can provide very high returns on investment.

The best way I’ve heard this kind of pattern summarized is “Earn while you learn.” In other words, create a feedback loop where your exploring informs your exploiting and provides regular returns on your increasing knowledge.

Parting Thoughts

You’ll notice that I called it the “Quality Pattern” and not the “Perfect Pattern” or the “Solved Pattern.” There is no single solution to the exploration-exploitation dilemma, and my simple models are not the be-all-end-all that some people might be looking for.

That’s why I called this “Managing the Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma” and not “Solving” it.

As I said in the beginning, this was written in blood to some degree. I’ve spent a lot of time getting this wrong. There have been periods where I went overboard with exploring, spending all my time philosophizing and navel-gazing instead of taking constructive action.

At other points, I let my desire to succeed override everything else and as a result I’d spend far too much time in an exploitative pattern of one kind or another.

In most cases, I can say with confidence that my problems were derived from fear of the unknown. When I was under-exploiting, I was too afraid of discovering that all of my “intellectual” labor wouldn’t survive contact with the real world.

When I was under-exploring, I was usually so terrified of failure that I didn’t realize that I would’ve been better off just accepting the inevitable and walking away sooner than I did.

Some critical relationships have been broken for me by these tendencies. I’ve crashed and burned more times than I can count. I’m getting older now, and it’s becoming harder to break free from my patterns. If anything, I hope what I’ve written here can get you wondering if you’re making the same kinds of mistakes.

Before ending this, I want to plant one seed in your mind about what all of this means. The seed is simple, but ever since I first encountered it, I’ve thought about it every single day. That seed is this: in most cases, you’re probably under-exploring.

There are exceptions here – some people, myself included, get trapped in over-exploration – and yet it seems that it’s the fear of the unknown that acts as the limiter for the majority of people.

For some of you, there is a very real risk in stepping outside the bounds of what you’re used to. Maybe you were born into poverty and you simply can’t afford to do anything else. I get it, and I don’t want you to take stupid risks that could put you on the street.

Just consider that you have a very small amount of time on this planet, and that the world is a big, incredible place, filled with all kinds of interesting people, places and things to do.

If you want to see your life change in a dramatic way, then it’s worth realizing that there are others out there who have probably already done what you want to do. This means it’s possible, in some ways at least, for you to do it as well.

I heard someone say one time that, in reality, we’re all specialists. Even if you’re a true “Renaissance Man/Woman,” you’d end up as a specialist just because there are potentially millions of things you could be doing at any given time.

A person who has mastered even a couple dozen skills (which never happens, by the way) would end up being a specialist from that perspective.

With all that in mind, I’ll leave you with this: don’t be afraid to step outside the bounds of what you’re used to. What you know and understand is comfortable and pleasurable, and what you aren’t aware of tends to be scary.

But chances are good that the risks aren’t as high as you think they are, and there’s a high probability that a better path is out there for you – if you’re willing to go look for it.